By Chathuri Senanayake D M, Dissanayake T

Abstract

Sensory ganglionopathy is an uncommon neurological disorder characterized by damage to the sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia. In this case, we present a rare and intriguing case of a previously healthy 26-year-old South Asian female who developed sudden hearing loss and progressive gait disturbance over a span of two months. Despite normal muscle tone and power, she exhibited marked reflex reduction, particularly in the lower limbs. The patient’s sensory axonopathy, confirmed through nerve conduction studies, suggested a diagnosis of sensory ganglionopathy. Interestingly, this case deviates from the typical presentation, as the patient did not exhibit the usual symptoms of sensory loss, such as numbness or loss of touch, vibratory perception, or proprioception. Additionally, the association of hearing loss with sensory ganglionopathy is unprecedented in the literature, making this case particularly unique. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges, the rarity of associated hearing loss in sensory ganglionopathy, and the positive response to early immunotherapy.

Introduction

Sensory ganglionopathy, also known as sensory neuronopathy, predominantly affects the sensory neurons within the dorsal root ganglia. [1,] Capillaries that supply DRG neurons have a leaky basement membrane, which enable the passage of inflammatory cells, toxins, and proteins. [2] In immune-mediated sensory ganglionopathy, available data shows that direct inflammatory damage to DRG neurons is mediated by CD8 T lymphocytes [7,8]. Humoral dysfunction seems to play a minor role in most forms, but anti-GD1b antibodies were associated to sensory neuronopathy in cell and animal-based models [9]. In immune mechanisms have been lately described in patients with idiopathic SN as well. We have recently found high IL-17 expression combined with reduced IL-27 expression in CSF lymphocytes.

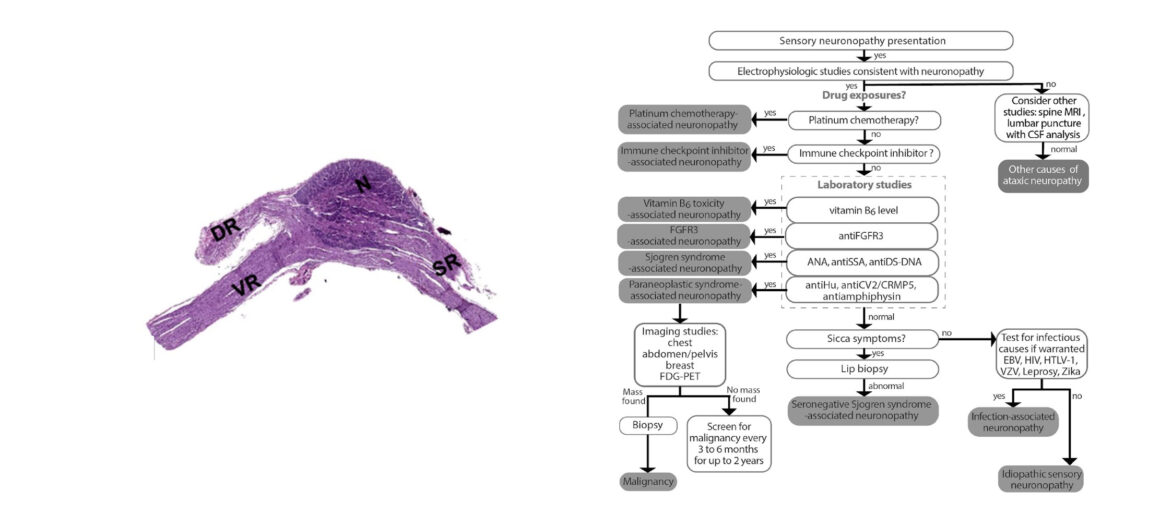

This condition is characterized by sensory ataxia, sensory loss, and a range of other sensory disturbances without significant motor impairment. Because the proximal projections of sensory ganglion cells form the posterior spinal roots that contain spinocerebellar fibers, ganglionopathies may cause a special form of ataxia that simulates cerebellar disease but without dysarthria and nystagmus. [1] If large nerve cell bodies are the main target of the disease, the ensuing deficit is mostly proprioceptive with sensory ataxia. [2,3] The disorder may present in association with systemic diseases such as paraneoplastic syndromes, autoimmune diseases, or infections, but can also occur idiopathically. In most cases, sensory ganglionopathy manifests with autonomic dysfunction is also commonly reported, given that the sensory ganglia are in close proximity to autonomic ganglia, which may also be affected. [1,3] The clinical course of sensory ganglionopathy can vary, ranging from a rapid progression over days or weeks to a more insidious onset over several years. Severe sensory ataxia impairing control of limb movements can be misinterpreted as muscle weakness, prompting the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Unlike other immune-mediated neuropathies and ganglionopathies, there are no available immunological markers for sensory ganglionopathy.[3] Thus, the diagnosis and treatment are frequently delayed. Imaging studies, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may show abnormalities such as swelling or increased signal intensity in the dorsal root ganglia on T2-weighted images, as well as degeneration of the posterior columns in the spinal cord. Nerve conduction studies typically reveal reduced or absent sensory nerve action potentials, with relatively preserved motor function, which is critical for diagnosis. The condition is more prevalent in females and can present at any age, although it is more common in middle-aged adults.

This case report presents an atypical presentation of sensory ganglionopathy in a young, previously healthy female, with hearing loss. The patient’s case provides valuable insights into the diagnosis, management, and potential outcomes of sensory ganglionopathy, particularly in cases where early immunotherapy is initiated.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy 26-year-old South Asian female presented with a two-month history of progressive gait impairment and imbalance. Initially, she experienced difficulty in walking, described as “dragging her feet,” which progressed to the point of being unable to sit up or walk unaided. Concurrently, she developed hearing loss that gradually worsened over several weeks. The patient denied any voice changes, autonomic dysfunction, or sensory numbness.

On examination, her muscle tone and power were normal, and there was no evidence of central nervous system involvement. Reflexes were markedly reduced in the bilateral lower limbs, with intact reflexes in the left upper limb but diminished reflexes on the right side. Despite diminished reflexes, her sensation to pain and light touch remained unaffected, and her gag reflex was preserved. The patient had no significant medical history, recent infections, or known allergies.

Investigations

Initial investigations included a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, thyroid function tests, calcium levels, liver function tests, electrolyte levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), all of which were within normal limits. Serum vitamin B12 levels were normal. Autoimmune workup, including antinuclear antibodies (ANA), was unremarkable. Tumor markers CA 125 and CA 19-9 were slightly elevated.

Imaging studies included contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scans of the brain, CP angle, Internal auditory meatus appears normal, CECT chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were largely unremarkable, except for a small, indeterminate nodule in the middle lobe of the right lung. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spinal cord was normal. CSF analysis revealed no abnormalities.

Nerve conduction studies showed normal motor nerve conduction in both upper and lower limbs. However, sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) were absent in the lower limbs and showed low amplitude in the upper limbs, suggesting a diagnosis of sensory ganglionopathy. The absence of significant autonomic symptoms, preserved muscle power, and lack of pain were notable, especially considering the patient’s hearing loss, which is not typically associated with sensory ganglionopathy.

Treatment and Outcome

The patient was started on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. Within one month, she showed marked improvement in sensory ataxia, and after three months, she was able to walk without support. However, her hearing loss did not improve. This case demonstrates that early immunotherapy can halt disease progression and lead to significant improvement in patients treated within the first three months after symptom onset.

Discussion

Sensory ganglionopathy poses significant diagnostic challenges, especially in atypical cases. The archetypal presentation involves a combination of proximal sensory symptoms and sensory loss with ataxia, all while preserving muscle strength. This condition is often confused with cerebellar ataxia due to the profound gait disturbances and loss of proprioception it causes. However, unlike cerebellar disorders, sensory ganglionopathy typically does not present with dysarthria or nystagmus.

The pathophysiology of sensory ganglionopathy involves the degeneration of sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia, which disrupts the transmission of sensory signals, particularly those related to touch, vibration, and proprioception. Disease processes affecting the sensory ganglia often also impact the autonomic ganglia, leading to symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, and gastrointestinal dysmotility. In this case, the absence of autonomic dysfunction was unusual, adding to the complexity of the diagnosis.

Interestingly, this patient did not exhibit some of the classical features of sensory ganglionopathy, such as the loss of touch, vibratory perception, and proprioception. Additionally, hearing loss is not commonly associated with sensory ganglionopathy and was not found in the literature review of similar cases, making this case particularly unique. The cochlear nerve, responsible for transmitting auditory signals from the cochlea in the inner ear to the brain, could be affected by the same pathological processes that damage the sensory ganglia. This could lead to sensorineural hearing loss. Since sensory ganglionopathies typically involve large sensory neurons, if the disease process extends to the neurons of the cochlear nerve, it could impair hearing.

MRI findings in sensory ganglionopathy can sometimes reveal swelling or increased signal intensity in the dorsal root ganglia on T2-weighted images, or degeneration of the posterior columns of the spinal cord, though this was not observed in this patient. The preserved normal muscle power and the absence of significant autonomic symptoms further distinguish this case from more typical presentations.

The therapeutic response to IVIG in this patient suggests that early immunotherapy can be effective in halting disease progression, even in cases where the etiology remains idiopathic. Most cases of sensory ganglionopathy evolve rapidly over a period of days or weeks, and the importance of early intervention cannot be overstated. The patient’s significant improvement in gait and balance following IVIG therapy highlights the potential for immunotherapy to stabilize the condition and prevent further deterioration.

The importance of sensory ganglionopathies in general medicine lies in their association with underlying systemic diseases, such as paraneoplastic or autoimmune conditions. Approximately half of the cases remain idiopathic despite extensive evaluation, as was likely the case here. Idiopathic sensory ganglionopathy is more common in females and can present at any age, though it is typically seen in middle age. The disease can progress rapidly or insidiously, and while some cases may resolve spontaneously, others follow a chronic or relapsing course.

Conclusion

This case underscores the importance of considering sensory ganglionopathy in patients presenting with unexplained sensory deficits and normal motor function, particularly when standard investigations yield inconclusive results. The positive response to immunotherapy in this patient highlights the potential for early treatment to improve outcomes in sensory ganglionopathy, even in atypical presentations. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between sensory ganglionopathy and hearing loss, as well as to identify optimal treatment strategies for this rare condition. The unique presentation of this case, with hearing loss and a lack of typical sensory deficits, emphasizes the need for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion and consider sensory ganglionopathy in a broad differential diagnosis.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Reference

- N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1657-1662, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2023935, VOL. 383 NO. 17

- Martinez ARM, Nunes MB, Nucci A, França MC Jr. Sensory neuronopathy and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune Dis. 2012; 2012:873587. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Camdessanché JP, Jousserand G, Ferraud K, Vial C, Petiot P, Honnorat J, Antoine JC. The pattern and diagnostic criteria of sensory neuronopathy: a case–control study. Brain. 2009; 132:1723–1733. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Donofrio PD. Textbook of Peripheral Neuropathy. 1. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Pareyson D, Sghirlanzoni A. Neurophysiological diagnosis of acquired sensory ganglionopathies. Eur Neurol. 2003; 50:146–152. [PubMed]

- Horta CA, Silva FG, Morares AS, et al. Profile of inflammatory cells in the CSF and peripheral blood, expression of IL-17 and IL-27 and T cells mediated response in untreated patients with idiopathic ganglionopathy. Neurology. 2011;76, abstract A464 [Google Scholar]

- Camdessanché JP, Jousserand G, Ferraud K, et al. The pattern and diagnostic criteria of sensory neuronopathy: a case-control study. Brain. 2009;132(7):1723–1733.

- Sghirlanzoni A, Pareyson D, Lauria G. Sensory neuron diseases. Lancet Neurology. 2005;4(6):349–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa T, Miyatake T, Yuki N. Anti-B-series ganglioside-recognizing autoantibodies in an acute sensory neuropathy patient cause cell death of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;157(2):167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntzer T, Antoine JC, Steck AJ. Clinical features and pathophysiological basis of sensory neuronopathies (ganglionopathies) Muscle and Nerve. 2004;30(3):255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny-Brown D. Primary sensory neuropathy with muscular changes associated with carcinoma. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1948; 11:73–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leave a Reply